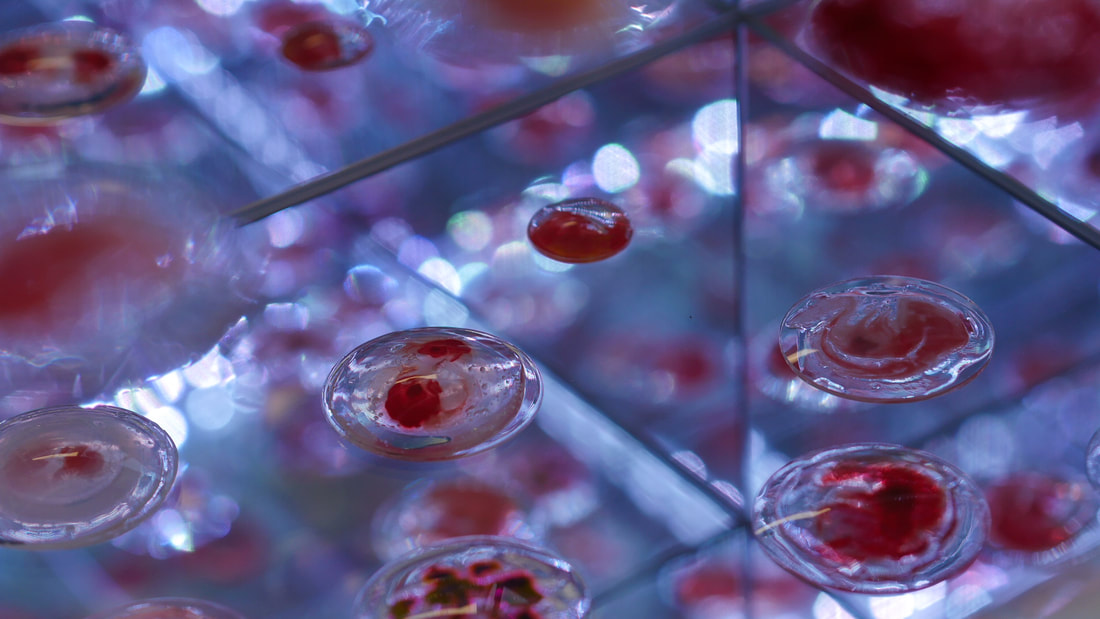

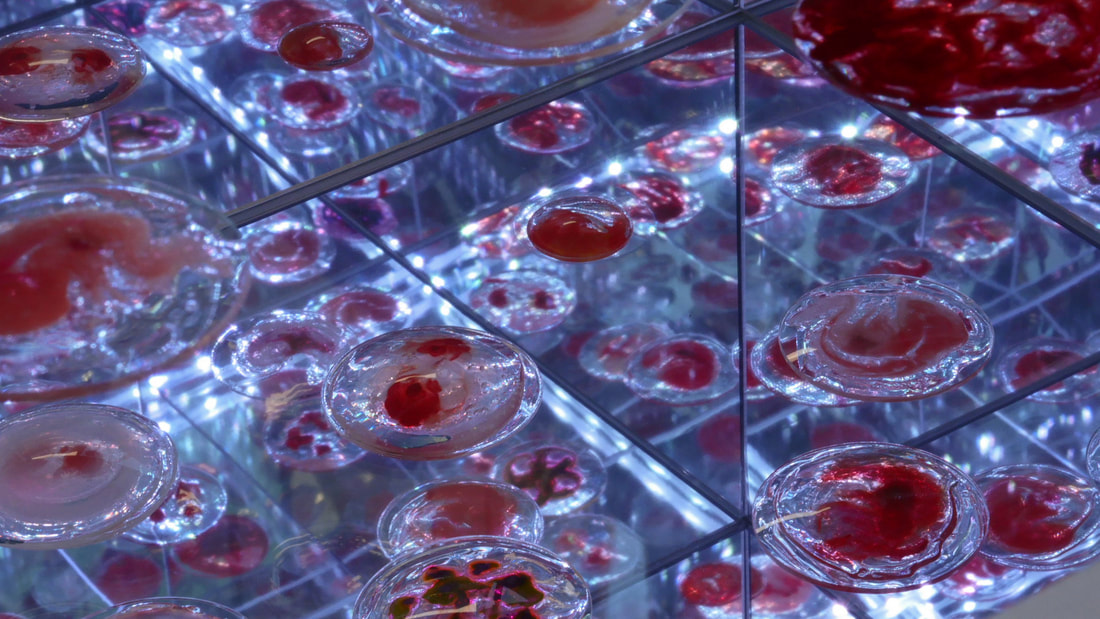

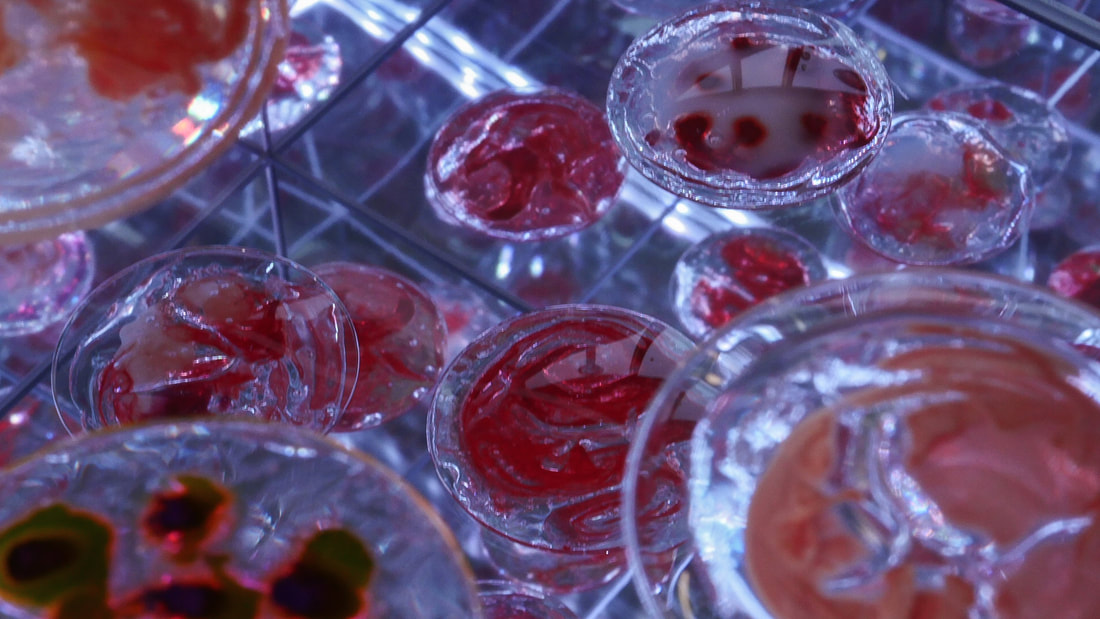

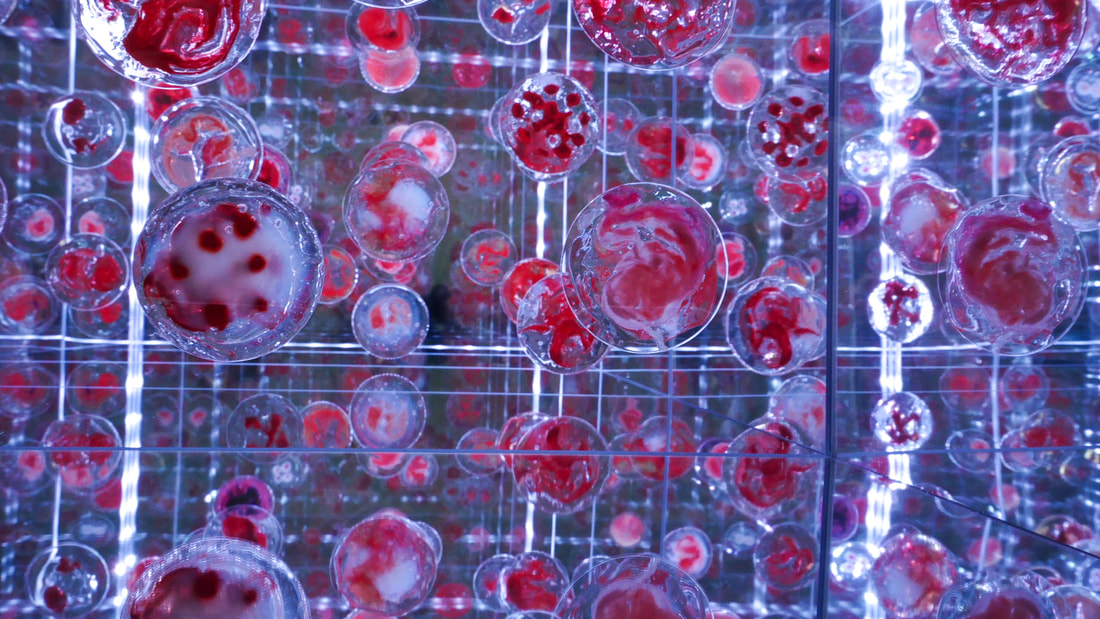

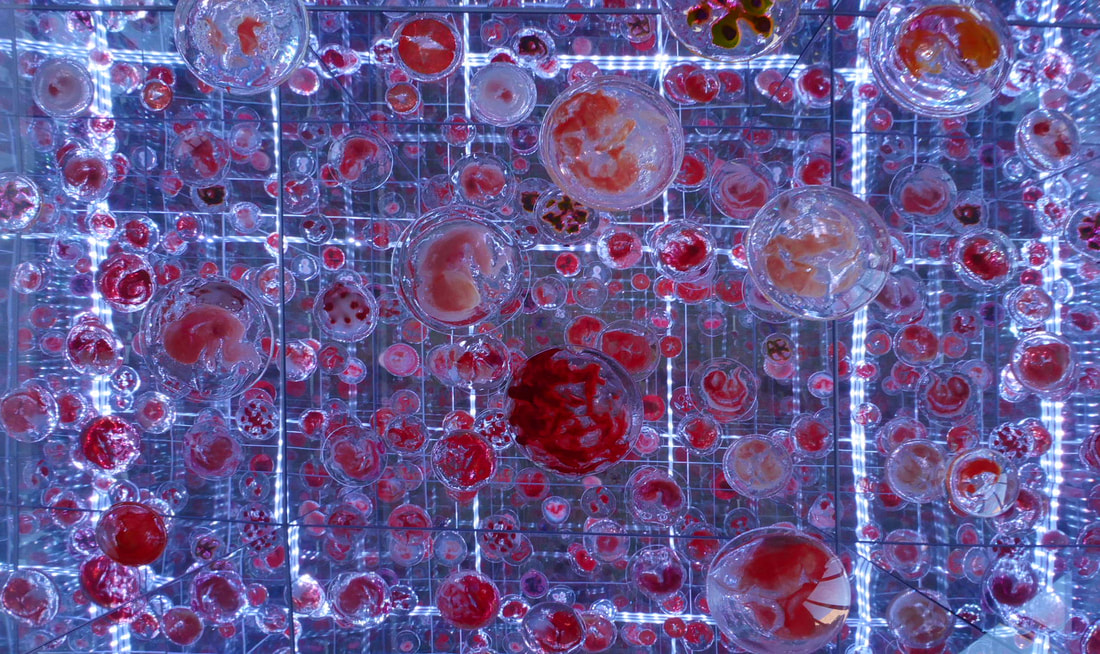

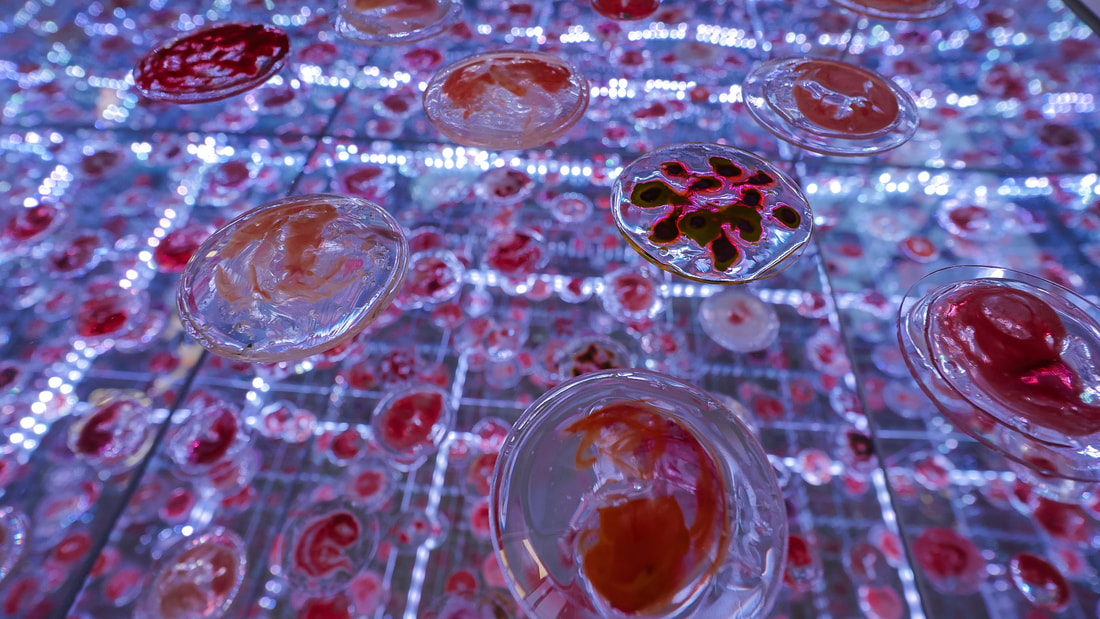

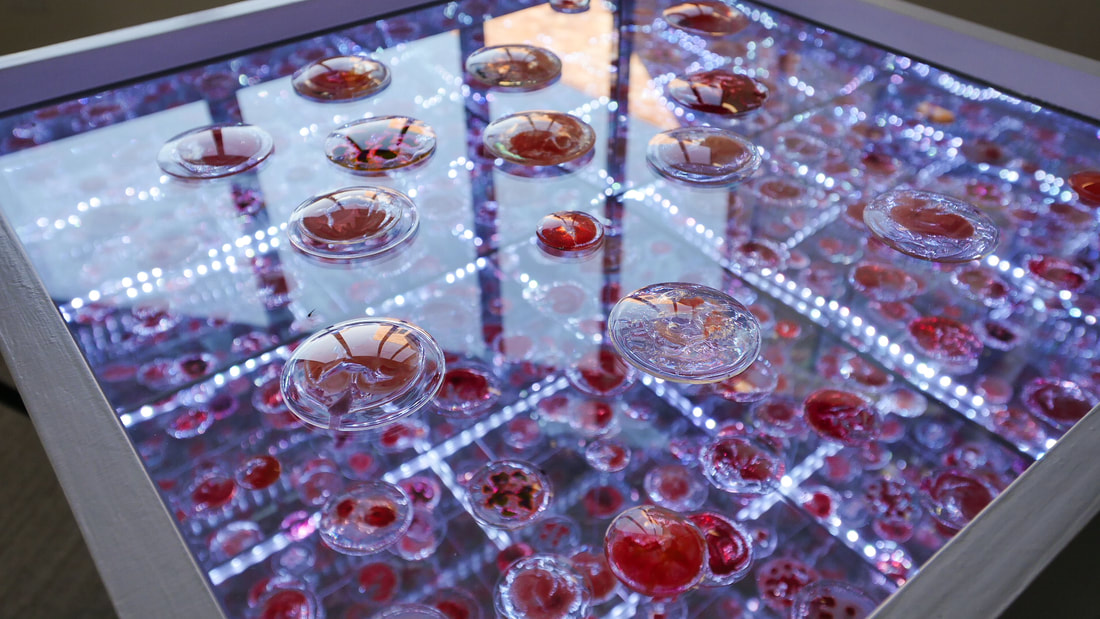

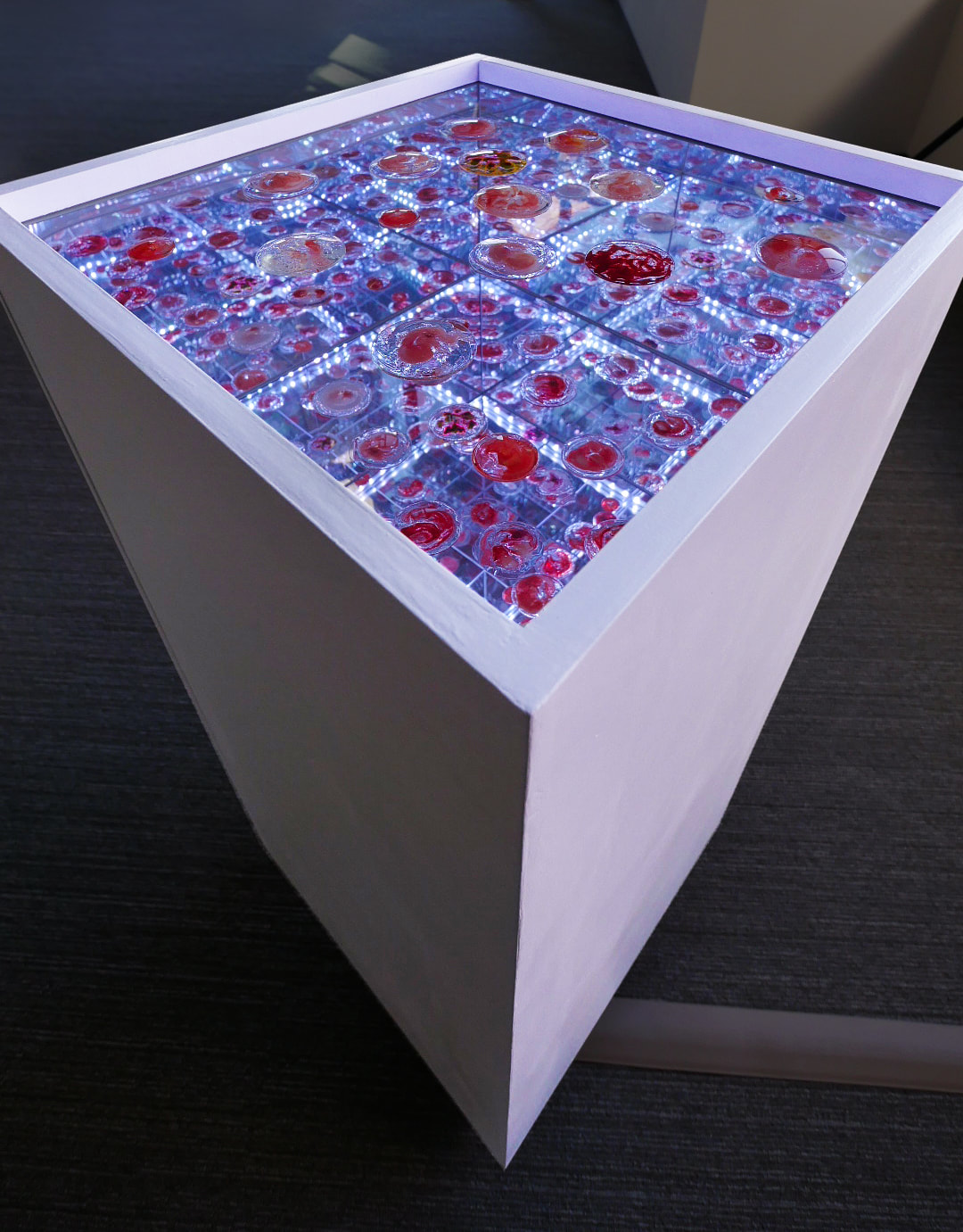

The desire for, and the impossibility of, infinite expansion

wood, glass, polymer medium and acrylic pigment on watch glass/ beaker-covers, LED lights

18"x18"x38"

2018

wood, glass, polymer medium and acrylic pigment on watch glass/ beaker-covers, LED lights

18"x18"x38"

2018

© Catherine Cartwright 2018

"Man is always seeking to expand himself, to pursue greatness." - Indian mystic

"Life Will Colonize." - Robin Hanson, Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University

The nature of life is to expand itself, to seek ecological opportunities, and to live long enough to reproduce. Humans are unique in the fact that we seek to expand ourselves for reasons beyond mere survival. We expand ourselves to satisfy drives of the ego such as seeking power, status, or immortality. A lion doesn't dread death, aspire to colonize mars, or deny the holocaust.

We expand our personal empires with the hope that our name, reputation, and familial lineage will live forever. Our desire to expand ourselves often supersedes our concern for others and for the collective survival of our species. One might argue that humans are unique in their desire for over-expansion, and that our lust for comfort and pursuit of immortality makes us uniquely vulnerable to the threat of self-destruction. Human-kind has a fantastic capacity for complex cooperation, yet our past is fraught with examples of systematic self-harm. Perhaps we are confused.

On a cellular level, cancer cells also confuse their relationship to the body and become obsessed with immortality. Cancer cells have developed in a way to defy death, to infinitely expand until it destroys the very environment it relies on for survival. If overexpansion is self-destructive at the cellular level, could it be self-destructive for humanity at the societal level? What if the desire for over-expansion is a biologically-wired kill-switch for our race, timed in such a way where we are destined to destroy our host environment and ourselves before we have an opportunity to spread further?

At our current evolutionary stage, according to the "Great Filter" theory, the next logical step in human evolution would be to overcome our dependency on our single planet and to colonize the galaxy, becoming infinite as a species. Physicist Enrico Fermi posed the paradoxical question, “If the mathematical probability that intelligent life could evolve in other parts of the universe is so high, where is everyone?” Why has no one else conquered the galaxy yet? We would know if we were colonized, right? What is stopping other species from reaching this stage of intergalactic expansion? Could there be an evolutionary glass-ceiling?

The Great Filter theory supposes that maybe after a species gains the technological ability to dominate its own planet, it also co-develops the ability to destroy itself, and then does. Along with the intelligence, creativity, and technological development required to travel space, brings with it an inherent lust for unsustainable expansion resulting in unintentional self-destruction. In other words, technologically advanced beings are likely to ultimately destroy themselves before communicating with, or colonizing anyone else.

Is it odd that we developed the capability for nuclear destruction and space exploration almost in the same breath? We are faced with two scenarios. Either we have reached the end of the line, and we are doomed to self-destruct like all the others, or we are the first to pass this point- this great filter. If we are special, and we manage to avoid the terrifying threat of self-destruction, we may actually be closer than any other species in existence to the possibility of becoming masters of the universe. We could actually be standing, in this very moment, at the threshold of infinity.

This piece explores the aesthetics of embryogenesis and possibilities for mutation and disease in the context of the idea of infinity. Abstracted imagery inspired by cellular replication and embryonic development are painted with acrylic pigments in a body of polymer medium on chemistry watch-glasses. The aesthetic of scientific observation is often cold, clinical, and removed from references to the host-body- the mother, avoiding contending with the social relations bound up in the formation of an embryo and the reproduction of the human species. Without the body, we look at human material in the abstract as it may appear to be forming or deforming into a human being, and the fate of these hypothetical specimens in the current environment is highly questionable.